Living in Beijing: a suburban topography

This field research explores the housing situation in Beijing through a series of interviews aiming to juxtapose the living conditions of local residents and their housing typologies. Fifteen families or individual inhabitants living in different neighborhoods of the capital agreed to be interviewed in the privacy of their homes, to share their habits, their living conditions, their relationship with their homes and their immediate environment.

Initially aiming to expand our common understanding of the issues and challenges Beijing inhabitants face in relationship to their housing, this approach also revealed the hopes and daily pleasures of an urban life which at times is difficult. The analysis of the different housing typologies and construction types occupied by the interviewees also emphasized the changes the city has undergone in recent decades.

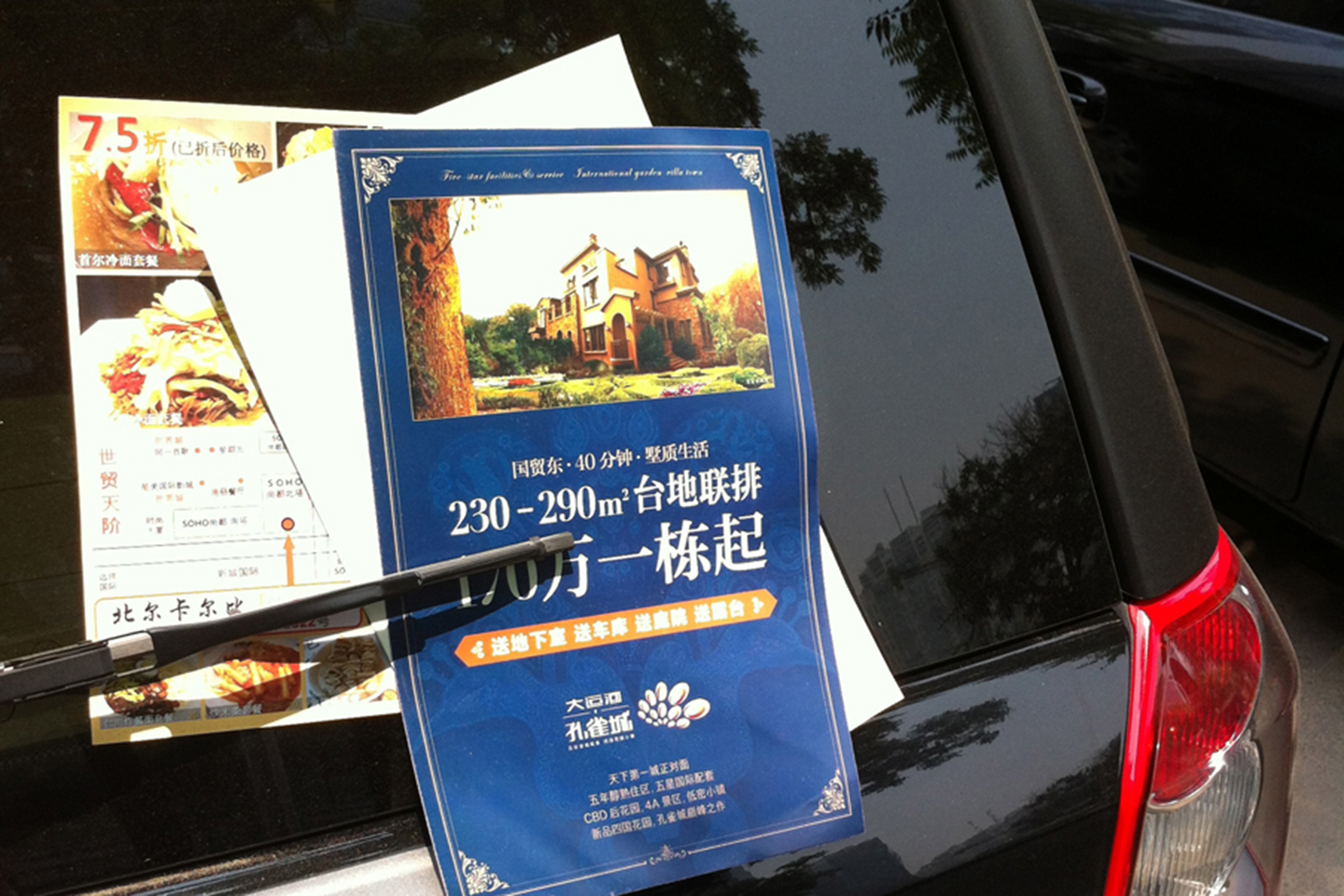

Through the singular stories of three families located in the outskirts of Beijing’s city center (Shunyi, Tongzhou, Changping), Mrs. Cyr presents us with the first results of her study. Her findings present a landscape where aggressive marketing strategies are contributing to the fragmentation of the social and physical environment, and seemingly prevailing over any long-term logic regarding the city’s urban development. In this case, image is at the chore of the transformation process of the city.

City Development in a Marketing Background

For more than five decades, urban housing has been managed by the Chinese government[1]. As a consequence of the introduction of property rights following land reform in the 1980s in China, housing has turned into a prized commodity. The Chinese real-estate market greatly benefited from this boom; numerous luxury-housing complexes have emerged throughout Beijing, creating a new image for the city and pushing advertising’s boundaries even further in an attempt to boost sales.

Potential buyers looking for a home usually consult real estate websites – Sina real estate site, Soufun, Dooland, etc – where it is easy to compare different purchase options. Crowds of potential buyers also attend the thousands of real estate fairs held biannually; these huge events bring together developers from all over the country. With aggressive sales methods, these property developers use digitally enhanced and polished images of large villas nestled in large green spaces, their manicured landscapes reflecting in crystal clear ponds of water.

Posted on the entire length of the tall fence surrounding residential areas under construction, these same pictures occupy a huge amount of the city’s visual space. Oversized, their presence often generates a strange sense of distance from their context. Thus, through this constant visual repetition, a dream city is being built; first bi-dimensionally in the collective unconsciousness, then implemented into a reality of concrete, dust and noise, dryer and harder, and mostly, significantly less “sweetened” than its paper-thin version.

In this utopian universe, the question of style is a strong marketing factor that often guides the consumer decisions. Even if inaccurate, every developer develops its own vision of a foreign residential urbanism; in turn, villas freely borrow English, Spanish or German aesthetics. In an interview, the architect Qi Xin expressed his disappointment about working with developers in China who systematically replicate successful models without any innovation or originality. Architecture here has been transformed into a fusion recipe where diverse and discordant ingredients must be combined – English gardens, Chambord roof and turrets, stone and wood, Greek columns, fireplaces and high ceilings.

Whether located in the city center or the suburbs, new real estate projects creatively use extremely evocative commercial iconography – pictures of a rural communal life. On this matter, Wu Fulong, in a recent article on the new Chinese suburbs[2], explains that the ideal community such as the one promoted by developers aims exclusively at the wealthy population. The break is not only spatial, but also social. The real estate project, cloistered and disconnected from its environment, is introduced and sold as an entity capable of increasing a social status and creating a new form of identity. Far from fulfilling this identity search, the result often leads to the reverse, and surreal impression, as though one were entering a theme park. This approach is so widespread that it is possible to consider this stereotyped production as a predominant feature of any residential architecture in contemporary Chinese cities. Nevertheless, our investigation has shown that there are significant gaps between digitally enhanced pictures and reality, even in the most sought-for residential areas. As for developers, the most essential thing remains sales.

In Shunyi, one of the eleven new towns built a decade ago in the outskirts of Beijing, this version of the suburban dream seems to set a new accommodation standard. Luxurious housing complexes have multiplied, each of them enhancing a vision of the ideal city in their own way: spacious and located in a low-density environment where each villa is accompanied by its own private garden. Some of these residential houses are recent or about to be completed, while others completed a few years prior already show signs of decay. The villas, either isolated from each other or arranged in alignment, are surrounded by a protective wall providing residents with a safe living environment, where only an extremely well planned environment is perceptible to the outside eye.

In these islets, despite the extremely low crime rate in the city, security is presented as essential[3]. Rather, enclosing and restricting access to these residential places is a way of creating living standards corresponding to the aspirations of an urban elite while creating an image tinged with exoticism, luxury and remoteness.

Beijing’s customized habitats for the privileged

Although the acquisition of property is a real aspiration for most people in Beijing, this “dream” is difficult to realize. Prohibited up until the late 1980s, buying residential property is now only possible for the wealthiest. Indeed, with a per square meter price[4] that can compete with that of major French metropolises[5], the average annual salary for a Beijing resident [6] is far from enough to invest in real estate. Moreover, payment conditions are becoming increasingly draconian: a minimum down payment of 50% of the house value can be requested upon purchase, the remaining balance to be paid within the next three years [7].

Despite these difficulties, some are willing to make tremendous sacrifices in order to own a property. Some families save for several years, and sometimes, an entire generation must sacrifice their own well being to allow their offspring to own property. The emergence of a rhetoric promoting an imported urban model is reflected by the transformation of the urban landscape inherited from the socialist period. Well beyond a simple image change, it is about the search for a new and suitable model for a social class that did not previously exist in China. This new bourgeoisie aspires at distinguishing itself from the masses housed in high-density units and apartments in the city’s core.

Regardless of the family’s standards, the living environment remains a decisive factor in the choice of accommodation. The two case studies of two families provides insights about the gap between the residents’ dreams and the reality of their homes. The third interview illustrates a different situation because the “privileged” residential setting was accessed through rental.

True life-choice or a family compromise? Interview with Ms. Chen in Shunyi

The Chens’ children attend one of the most prestigious private international schools in Beijing. In order to gain admittance to this school and give their children the best possible opportunities, the family temporarily immigrated to Canada where they obtained new citizenship. Upon their return, the Chens settled near this school in the heart of Shunyi, a new district North of Beijing (Beijing’s municipality has a total of 11 city districts), where a large majority of expatriates and international schools are located. In addition to the draws of the location, the possibility to purchase a 860m2 home in a luxurious complex is clearly a symbol of prestige and social success and consequently influenced the family’s choices.

Made up with imposing “neo-Chinese” style villas, the neighborhood is built around an artificial lake. But Chen’s house, which is at the limit of the complex, is not only deprived of this view of the lake, but instead overlooks various temporary barracks from nearby construction sites.

Despite this conscious decision, Ms. Chen is not completely satisfied with her new life and her home. Instead, she feels relatively isolated from her six family members that she rarely meet anymore. She speaks of her friends that live on the other side of the complex, where houses are arranged in alignment and much closer to each other, thus facilitating friendships and relationships. She tries to convince us, perhaps without actually believing it herself, that her house is relatively “simple”. She takes us through a game room devoted to table tennis, another one dedicated to billiards, where the table is disproportionate. We then make it to the terrace, which does not seem like it is used very often. From here you can admire a basketball court adorned with life-size effigies of her son’s favorite players. The 15-seat home cinema, elaborate elevator, grand piano, and three reception rooms comfortably furnished with sofas in a heavy-handed European style, are all there to impress. Upstairs, the rooms are divided into two, their excessive size making them difficult to decorate. A drawing room, a ballet room, a computer room and office are adjacent to the individual bedrooms, each decorated to the specific taste of their occupant. They have at their disposal an apartment with rooms dedicated to their leisure, entertainment and rest, to the despair of Ms. Chen, who admits feeling bored and lonely in such a big house, despite the presence of her husband, two children and her parents.

She rarely goes into town, preferring to shop and go out within the area of her home. Mrs. Chen entrusts us with her sincere feelings and thoughts, explaining that she does not really like Beijing, its traffic and pollution, and anxiously awaits the day when she will return to her native town in Guizhou. For the Chens, life in Beijing is temporary, as they will probably relocate to the south of China once the children leave for university. She not only prefers the climate in the south, but also the mentality of the people. Her husband, who made his fortune in the stock market, does not need to be based in Beijing for his work. Finally, for the Chen family, living in Beijing does not represent an ideal life in itself, but rather a means for their children to enjoy an exceptional living environment and good studying conditions.

Housing as a new beginning. Interview with Ms. Li in Tongzhou

The story of Li Wenyu, who is from a different social class than the Chen family, is also interesting. She chose to live and to invest in the purchase of an apartment in Tongzhou, a new city southeast of the capital, at the edge of the sixth ring road. Like many other Beijing residents who do not want to remain tenants all their lives, she had to move away from the city center in order to gain access to a property. As such, she decided to go into exile on the outskirts of the city where a wide choice of accommodation in new complexes is offered.

Early in her career, Li was promoted to the position of professor at Wuhan University. She left this prestigious career a few years later to try her chances in Guangzhou. There, her English skills allowed her to get a highly paid job (ten times better than at the university) in a foreign company. She quickly moved up in grades, and a few years later got hired by a competitor, also a foreign company. Having been in so much frequent contact with foreigners over the years, Li has become westernized as evidenced by the furnishing and décor in her apartment.

She went to many real estate fairs in search of the best deal, finally opting for a Singaporean developer who already had completed several projects in Guangzhou. She bought her apartment before market prices went up (after 2009) and acquired 93 m² for the price of 10,000 Yuan/m². She bought it before construction was completed, while the developer was still putting up apartments for sale one-by-one in order to control prices. But today, despite the initial expectations of an important capital gain, like many other real estate complexes in Beijing, Li in fact will barely be able to recoup the original value her purchase.

As she is a single mother, her decision to buy an apartment was primarily motivated by practical factors, such as the distance to her work place, to the international school her child attends, and particularly, that her new house would be entirely finished and equipped with a kitchen and sanitary facilities[8].

For Li Wenyu, living in Tongzhou also provides rapid access to her work in the BDA[9]; a privileged investment zone south of downtown. But this small satellite town remains underdeveloped: most of the buildings are still under construction and the area’s facilities are still significantly lacking. Li spends her weekends outside her area strolling through shopping malls in the city center. After all, Tongzhou is a dormitory town that has failed to meet any of the promises of the developer.

Finally, the insufficient and sparse surroundings give her a sense of alienation quite similar to Ms. Chen’s. For Li Wenyu, the way the projects are presented in real estate fairs raises a problem. These large biannual events in large exhibition halls bring together foreign investors and potential buyers. Yet most of the projects showcased by these events are either not yet built or quite distant from reality.

« Temporary long term migration »: Interview with Mr. Liu in Changping

The experience of living in the city can be different for each individual. Some, like the Chen family, come for better living conditions for their children; others, like Li Wenyu, fight for a professional career, while others receive training or open a business and make a fortune, without ever considering settling there permanently.

This is the case with Liu Ke, a retired public service employee who chose to come to Beijing to work for only a few years. The pension he receives in Shandong is reasonable[10], but he hopes to quickly earn more to buy a house for his son. He also deeply loves the capital because this city allows him, as a historian, to bathe in a cultural environment he cannot find in his hometown. He chose to rent a place a place for an affordable price in the northern suburbs of the city, in another new district called Changping. The housing complex promised great benefits: Internet, heating, private bathrooms, hot water, etc.

But for a monthly rent of 500 Yuan for a 15 m2 room, one might expect a different reality. Access to the complex is difficult and restricted due to series of military installations and the proximity of a nearby village in the midst of demolition. One must walk along a long open and pestilent sewer canal, a route that is likely worse in the summer heat. The complex consists of a series of 4-floor buildings forming two “E”s connected by a footbridge. To get there, we pass under a advertisement banner and an entry security post where many screens broadcast images from cameras hidden throughout the site.

In fact, the contrast between the banner and the reality of the site is quite shocking, even more so when one enters the complex and realizes that the corridors have no actual doors, but simply thick sheets covering the entrances to provide some protection against the wind.

Nevertheless, Mr. Liu is satisfied with his situation. At times, some of his historical research can be done from his computer, which saves a 40 minutes trip into the city center. He and his wife meet regularly. He proudly shows off the small pair of sandals that await her next visit. He offers us apples he has prepared in a small corner that has been transformed into a kitchen. Considering himself a temporary resident, his residence status suits him. For the same reasons, he feels neither need nor desire to make friends with the neighbors.

Conclusion

The image of the city is shaped well ahead of the construction of new buildings. Because it borrows numerous images of bucolic landscapes, which are widespread in real estate fairs, with advertisement posters providing an idealized and distorted image, and with housing complexes which shamelessly display a mixture of architectural styles and a loss of authenticity, the Chinese city is the result of an illusion that is constantly renewed. Moreover, developers actively deploy the symbol of globalisation to overcome the inherent contradictions of the housing commercialization in a post-socialist era. In a city with unbreathable air and disembodied urban areas, Beijing residents continue to buy, even at indecent prices, because they want to believe in a vision of a better world; like that of a powerful entrancing love potion, one that, in this case, is being proffered by real estate developers.

Notes

[1] “China’s Scary Housing Bubble”, The New York Times, April 14, 2011.

[2] Wu Fulong, in a recent article on new Chinese suburbs, explains the ideal community as promised, aims exclusively to have wealthy people. Fulong Wu, “Gated and packaged suburbia: Packaging and branding Chinese suburban residential development”, School of City and Regional Planning, Cardiff University, 2010.

[3] Up to the point where even photographing the interior from the street may be banned: the research team has sometimes been stopped.

[4] C. Cindy Fan. “The Upside if the Bubble Bursts”. The New York Times, 17 October 2011.

[5] http://www.meilleursagents.com/prix-immobilier/.

[6] “Beijing’s middle class expands to 5.4 million”, China Daily, 19 juillet 2010.

[7] Another notable element, which does not seem to be a dissuasive factor, only the right of usage is granted by the Chinese long-term lease system, and is limited to 70 years; the State remains the sole owner of the land.

[8] For any real estate purchase in China, the buyer is responsible for the installation of the kitchen cabinets, bathrooms fittings and finishes of the interiors. For smaller budgets, the work is limited to practical elements. For others, several thousand Yuan are often invested.

[9] BDA: Beijing Economic and Technological Development Area.

[10] Interestingly, in China, women retire at 55 years old and men at 60, while pensions correspond to full salaries. This pension system is primarily available for employees of State enterprises and their officials.

-

2018/02/28

-

Beijing

-

Isabelle Marie Cyr

the other map

Explore arrow

arrow

loading map - please wait...