The Visual Space of 798 Art District

There are two kinds of visual space; the first is space that exists in reality, and the second is imagined space. Anyone can see real visual space; some people see the objects in the space, while others see the structure of the space. Usually, space is not worth viewing for both its contents and structure, and the average person does not see anything unless there is some perceived value outside the visual.

The visual space of imagination

Artists must master the observation and representation of visual space. Using the most basic methods, two-dimensional artists sketch scenes onto flat planes. Sculptors mold materials into forms that add spatial tensions to an artwork. Conceptual artists can use a variety of dislocating methods to reflect visual forms, but the kind of visual space represented is determined by the artist’s personality, experience, and aptitude.

The second kind of visual space exists neither in reality nor in visual experience, but in the imagination. Imagined visual spaces transcend space, time, and all boundaries. However, many notable artists and novelists of the past have shown that space can be visible. Imagined visual space must transcend existence, otherwise these spaces cannot freely interact.

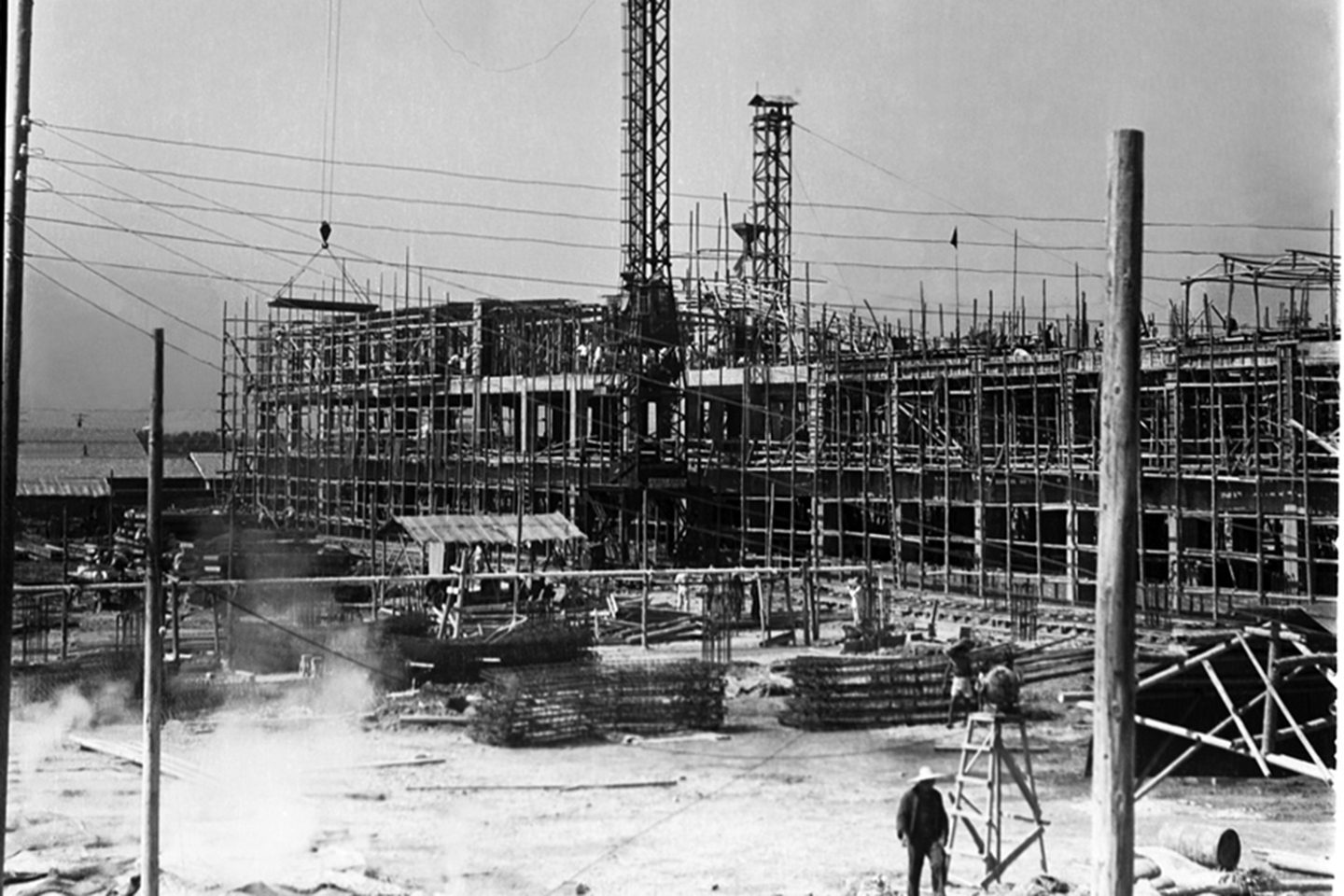

I moved into the 798, which was an old assembly plant in the 1950s, almost exactly ten years ago today. As such, I see the 798 from a rather unique perspective. However, I was unable to stay there because the visual imagination is transient and unwilling to set foot in real space. I simply remember that my imagination began with the recognizable history of space in the 798.

798 language

The 798 is located within a rapidly-changing urban environment. The period around the Olympics, from 2006 to 2009, was a test, and the gradual marketization of China’s economy presented an even deeper challenge to the 798. In addition, the 798 was influenced daily by shifts in national policy, tensions and relaxations in international relations, transformations in urban political systems, personnel changes among planners and mangers, cultural and artistic tastes, alternating trends, the relationships between professionals, collectors, and visitors, standards of interaction, psychological support, official will and planning, work targets, management styles, rules, regulations, and the sources and movements of capital. All of these factors combine in the unique environment that is the 798. Every situation has a unique complexity, thus, if we only summarize the 798 from one perspective, I fear that we will not accurately arrive at the language of the 798.

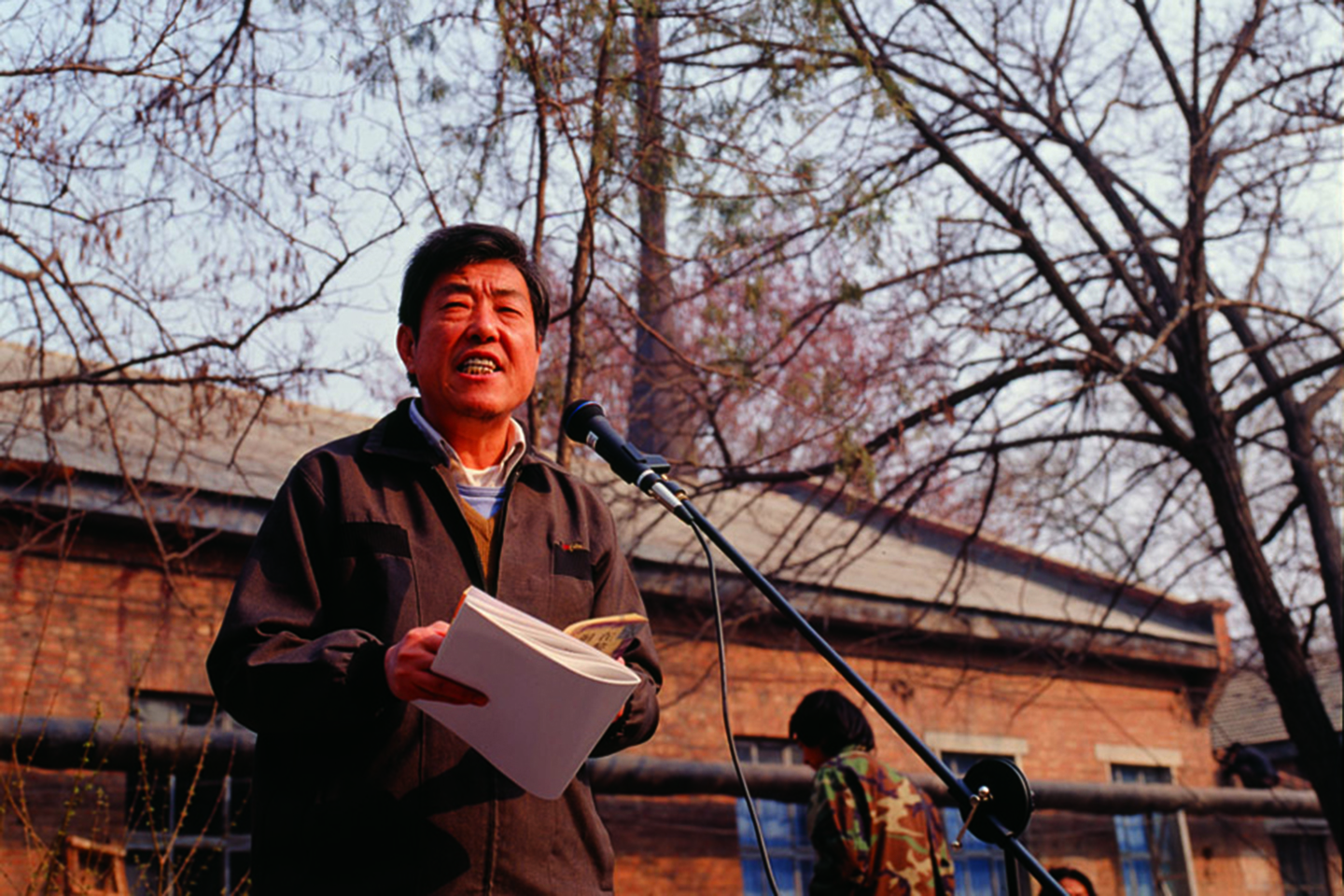

In 2007, I looked for answers to the changes and issues produced by 798’s past and present. I maintained an open dialogue with people in a wide range of disciplines, even if their various answers left much to be desired. The 798 has been rapidly commercialized, and I think that its superficial prosperity actually impacts its quality. The 798 has been greatly influenced by market factors, exhibition conditions, and common tastes. In this environment, it is difficult to recreate the high-quality experimental exhibitions that shocked the world and previously attracted world-class researchers and collectors to the 798.

Today no one opposes protecting the 798. What was intensely debated in the past has now become fixed policy. However, in the 798 and its surrounding urban environment, development takes priority over preservation and planning, while implementation focuses more on development. We can say that the 798 Art District is still developing, but that development must take place within the framework of preservation and respect for the context that made the 798. Its inherited industrial architecture needs preservation, but the organizations that renew historical architecture within a cultural context are even more deserving of preservation. The latter issue has never formally posed a problem because it is unrelated to the benefits of short-term development.

Where are the artists?

The 798 has many resources, some of which are obvious, such as its Bauhaus industrial architecture and its domestic and international fame. The 798 is also home to the richness of the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, the Iberia Center for Contemporary Art, Pace Gallery, and hundreds of other art institutions, galleries, coffee shops, bookstores, and gift shops. These can all be classified as “hard resources”, but this art district also has “soft resources”, such as the dozens of artists that once worked here, regular exhibitions (see the poster of Reconstruction 798’s exhibition designed by Wang Chao) and annual and seasonal art festivals, events, and performances. When large-scale exhibitions and art fairs open, many important international curators, critics, collectors, and artists come to visit the 798.

What is the primary driver behind the 798? The simplest answer is that the 798 continuously displays the free creative abilities of international capital. As a result of these abilities, ideas are communicated to an international audience, urban economic communities have an audience and focus to direct their excitement towards, and the economic realm is given the opportunity to utilize and capitalize on contemporary art. The 798 has also provided a place for the enlightenment and education of local contemporary art. Here, local art is packaged by galleries and provided to the market, popular market trends and consumption channels combine, and cultural products are consumed.

Creativity is rooted in human resources, which are the most important drivers of the 798’s continued development. Urban managers only see wave after wave of humanity, but another human resource cannot be seen and perhaps it will disappear if we no longer discuss the origins of the art district.

-

2014/06/17

-

Beijing

-

Huang Rui

the other map

Explore arrow

arrow

loading map - please wait...