Learning from a collaborative renovation of a dazayuan in Beijing

My studio Sinapolis has, jointly with the inhabitants conducted an original operation for the rehabilitation of a dazayuan. Located at the heart of Beijing, a dazayuan is a type of square and traditional courtyard, that has been strongly densified in the 1950s, but which is today very damaged. They currently represent 60 to 80% of the ancient center’s areas put under heritage protection. Understanding how these specific forms evolve is an elementary point if we want to bring solutions for the ancient center’s preservation. I hope my personal experience can demonstrate that a marriage between a participatory planning process with the local inhabitants and the respect due to the history of the existing site is possible. This article was published on the Chinese Portal of the New York Times, April 23, 2015: http://cn.nytstyle.com/living/20150423/tc23dazayuan/

Until the mid-2000s, it was very rare for a foreigner to live in the square courtyards of the historical center, especially in the ones shared between families, the dazayuan. The house I was visiting that day, was not even what we call a ‘’courtyard in a courtyard” (yuan zhong yuan), endowed with a wall surrounding the private sphere; this house was completely open to the neighbours’, and the property lines were blurrily drawn. The floor-tiles, the green 70s’ style tiles, the 10 meters-length single-storey and its spacious volume, the cypress stucked in-between two buildings, the feeling of an “inhabited landscape”: all of those features immediately won my heart. Although some interior work needed to be done, this good quality dwelling was sound and well-constructed.

I had then just arrived from Guangdong, after spending some time in Harbin and Shandong province for studying. I had never experienced a spatiality such as Beijing’s, where social ties follow the rules of a homogenous network of courtyards, mazes and alleyways, which combination creates a thick urban and human netting, on a surface equivalent to that of another urban gem: Paris, my hometown. The philosopher Heidegger established a semantic association between the words “build”, “be” and “inhabit”: in ancient German, these words have the same roots (bauen, bin). In Beijing, this layout in which the individual and the built environment melt into one body found its perfect application.

Degradations

It was not until early 2013 that the renovation of our dilapidated courtyard became necessary. The ground had become dangerous. The numerous layers of cement applied to patch up the several lumps in the ground turned to ice during winter to form a skating rink, hence making each of our movements difficult, especially for the elderly. In the summertime, the situation was no less complicated: shaped with ravine scoured up by the pouring rain of August, the ground was crumbling at every step taken. These arguments were enough to start a serious talk with the other owners about the maintenance of our maze. The continuous degradation of the courtyard was visible through some details, for which nobody seemed to care: the cypress had been cut, the main entrance was obstructed by bricks and garbage, water was infiltrating the walls, the awnings were turning yellow, a lean-to had been erected in the middle of the courtyard… the place that once appeared stunning was slowly changing into a ruin, and our common living space was shrinking away.

Yet, over time strong ties have grown between the inhabitants and me, I was not the laowai they pally hailed in the courtyard anymore; my young neighbours from Dalian were taking care of our 90-year-old doyenne during the evening or when their daughter could not come to Beijing (at 70 years old, she used to come by bus from Yayuncun almost every day to look after her mother). Our northern neighbours’ baomu fancied some talk about the rose bushes’ new blossoming. My landlords, who moved to the northern part of Beijing, also kept a friendly relationship with the other landlords. The pleasant atmosphere that overwhelmed the courtyard was in stark contrast to the decaying environment we were in.

For several months, the floor issue had been regularly raised, without any result. At best, the owners acknowledged that some renovation works had to be done, but they were worried about the costs that such big works would generate and therefore were constantly postponing the deadline. At worse, they thought that the situation was not that bad, and therefore that the restoration could wait for another few years. As a result of our discussions with the owners, I soon started to realize that two major impediments had to be overcome. On the one hand, some owners were suspicious of future changes in the protection plan for the historical centre (including our courtyard) and thereby intended to invest as little as possible in the maintenance of the courtyard. On the other hand, everyone wondered about the shape the possible rehabilitation plan would take: overall design, selection of the project manager, budget, co-ordination of activities…

For several months, the floor’s issue has been regularly raised, yet no results seemed to appear. In the best case scenario, the landlords reckon some renovation had to be done, but worried about the costs that such a work would generate and therefore constantly extended the deadline, in the worst case scenario, they thought that the situation wasn’t so bad, and therefore the restoration could wait for another few years. By dint of discussions with the landlords, I soon started to realize that two major impediments had to be overcome. On one hand, some landlords were suspicious of the possible changes a future protection plan for the ancient center could cause (including for our courtyard) and thereby intended to invest a minima in the frame maintenance ; on the other hand, everyone wondered what shape the possible rehabilitation plan would take: overall design, selection of the project manager, budget, coordination of activities…

Conception and rehabilitation works

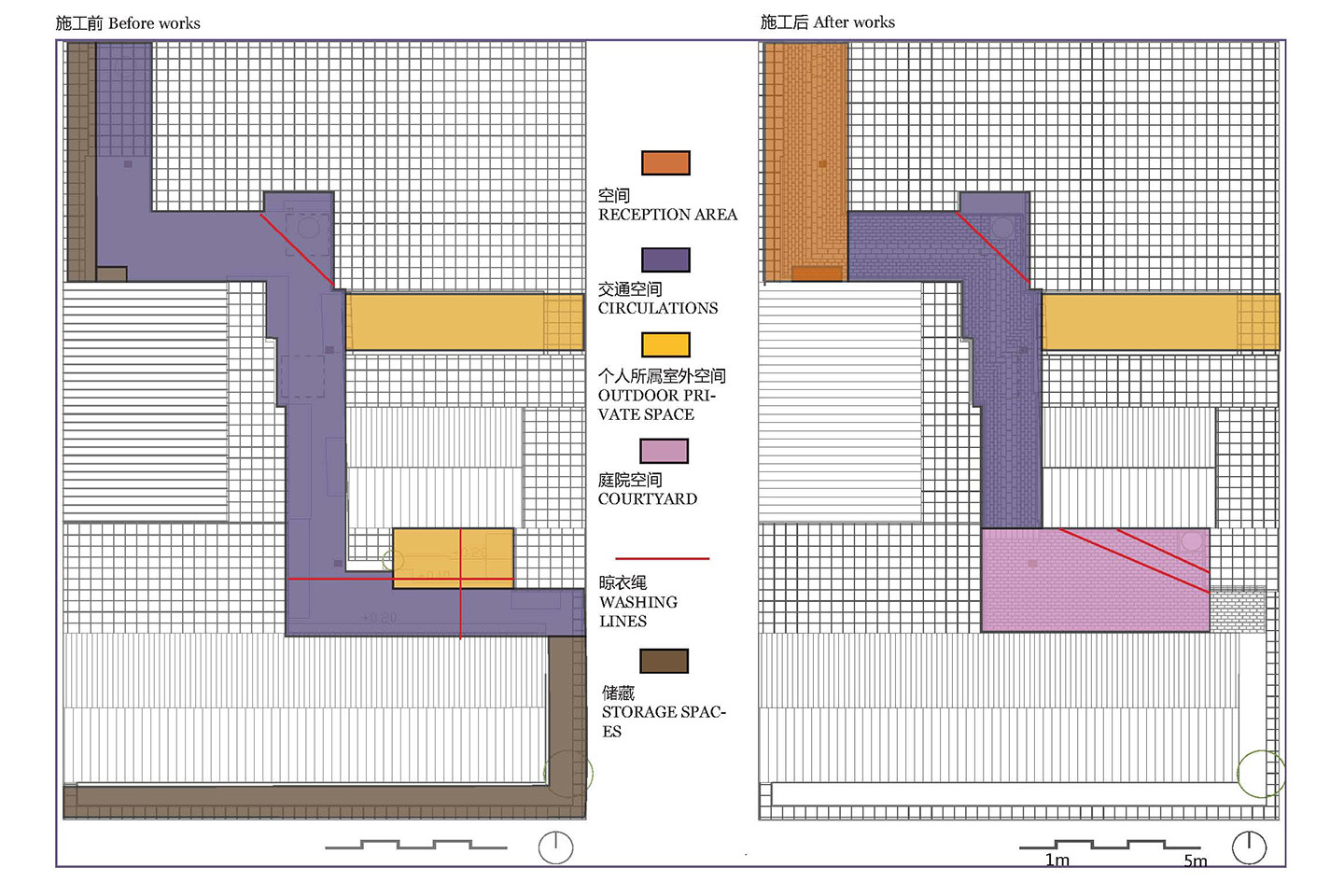

This situation gave to my studio plenty to think about. During the summer 2013, we proposed a game plan: by playing the collaborator’s role, we would take care of the whole rehabilitation (from the conception to the coordination), and would finance half of the total budget needed. Each landlord would equally finance the other half. We felt that the establishment of a co-financing was the best solution to get the landlords involved in the project process. Once the budget was fixed, our northern neighbour gave us an envelope containing her part of the budget, a malicious smile on her face, she said she hoped that this would foster the other landlords to do so. A few days later, the total amount of money was raised. We then organized a small reunion during which we exposed our plans to all the landlords. First, the floor had to be renovated by putting cement pavers that would follow a precise pattern, whilst respecting its existing inclinations; then, the main entrance to the maze should recover its original welcoming function; the shared space should be widened by putting aside the lean-to and the piled-up concrete slabs, so as to maintain the houses’ frontages (primer, insulation, carpentry, awning…). The renovation propositions were related to both the shared space and the landlords’ spaces.

However, it rapidly turned out that this notion of “shared space” we were using did not really exist. We erected this notion as a fundamental feature of the project, however the presence of some informal buildings (lean-to, cement pavers), precisely built within these “shared spaces” inevitably jeopardizes this reasoning. Yet, the idea to give a “shared space” back to the dazayuan worked its way through and became somehow accepted.

Other issues were then raised, for instance the location and the utility of the old septic tank, or the one of the air-raid shelter, dug in the 1960s, – had it been sealed? Where were the stairs that led underground…?

We encountered many problems during the renovation period. The first one was to clear out the rubbles generated by the ground destruction. At night, dump trucks had to come into the hutong in order to remove ten m3 piled up in the street, which required demanding logistics. Besides, a flea invasion, caused by the renovation fuss or by the uncontrolled dumps that attracted every kind of bug possible, made our daily life impossible for several weeks. The summer pouring rains also curbed the renovations, which ended only 3 months after they had started.

Feedback

In the end, at last, our courtyard eventually won the most beautiful hutong courtyard annual prize, awarded by the local Committee neighbourhood. This has of course enhanced our action and probably reinforced other inhabitants’ motivation to continue renovation works by themselves. And so forth, the movement was set off. Thereafter, a new front door to the maze has been set up, the several interior spaces which function used to be stockage have been put in order, the walls of the small interior courtyard were repaint as well. Creating a common space for a place that used to be a mere traffic lane seemed to give a new breath to this place, even though we’d still have a long way to go in order to enhance the general situation of the dazayuan.

More recently, following a conference organised by the Hutong Museum, who invited me to relate this experience, a Pekinese authority in charge of urban planning organised an official visit in the dazayuan. This visit, comprising approximately 20 urbanists, was very encouraging to me, although this project only represents an isolated move, and is in fine a mere renovation of a dilapidated environment, it nevertheless shows that a collective spirit can still prevail in a metropolis where individuals’ interests and mutual suspicions normally reign – especially when property ownership is at stake. It also shows that a good quality urban operation does not necessarily imply a huge scale intervention but can, on the contrary, be realised little by little at the local scale, at affordable costs and with a collective monitoring.

It is only after the renovation was done that the “micro-urbanism” concept, which is the idea of a proximity urbanism with the local inhabitants, appeared as appropriate to our action. We understood that the self-management practices that are actually taking place in the shared courtyards of Beijing are an undeniable virtue for the rehabilitation of the ancient center, on the condition that the inhabitants benefit from advices and references to improve their living framework and that professionals like us frame and coordinate the project, while respecting the daily customs already set up. We also realized that the interventions can be ranked in a pragmatic way, following the needs and the means available, that can go from minimal transformations (clearance and tidying up, destruction of useless lean-to, ground restoration, adding up lightnings) to architectural interventions (replacement of unsanitary buildings) and on common spaces – creation of meeting spaces, installation of common equipments, promotion of small gardens, arrangement of patterns of filled and empty spaces to give a new breath to the environment.

Chinese and French architects and urbanists who addressed this issue with me also thought about this approach from a theoretical point of view: is it possible to have a city-scale impact by intervening at the micro-scale? Studying the situation allowed us to identify the dazayuan as composing an informal hoop net, similar to most of the architectural typology of the ancient centre. It then appeared quite clearly that despite some difficulties such as their – sometimes – extreme density or insalubrity, those mixed private/public spaces, directly connected to the street, present interesting solutions at the urban level. Small living units can be found, the potential for social and functional mixity is quite high, tourism could also be substantially developed… Historically, the dazayuan embody sixty years of the city’s urban evolutions. Rather than try to get back to the perfect forms of the Ming or Qing dynasties’ traditional housing, we thought on the contrary, that it would be more interesting to rely on the organic character of these shared courtyards, born during the modern era and functioning as a creative and extremely powerful social network.

In Beijing, the dazayuan occupy the most significant part of the built areas. Consequently, it is essential for the renovation of this “ordinary heritage” to be urgently written in the municipality’s agenda, and it has to be achieved with the same energy required for the burying of the networks, the restoration and harmonization of the hutongs’ frontages. To this end, partnership-based financing between collectivity and landlords should be preferred; bottom-up inhabitants’ initiatives should be fostered, especially through information and awareness actions; urban regulations sometimes too flexible, sometimes too rigid should be reviewed on a case-by-case basis, so as to adapt to the multiplicity of the encountered situations; finally, and most importantly, a local professional and multidisciplinary frame – urbanists, architects, sociologists, economists, craftsmen, artists -, along with the inhabitants, should be set up in order to modernise and embellish this very particular urban typology before it fades away.

Other experiences, of small or large scopes, such as the ongoing revitalization of the Dashilan neighbourhood, prove that it is possible, and not without difficulties, to align local initiatives, heritage preservation and long-term development, in the interest of our city, Beijing.

Translated from French to English by Kimberley Le Pape

-

2016/04/19

-

Beijing

-

Jérémie Descamps

the other map

Explore arrow

arrow

loading map - please wait...